how to draw a 3d marble

Drawing is an fine art of illusion—apartment lines on a flat canvass of newspaper expect like something real, something full of depth. To achieve this effect, artists apply special tricks. In this tutorial I'll testify you these tricks, giving you the cardinal to drawing three dimensional objects. And we'll do this with the help of this cute tiger salamander, as pictured by Jared Davidson on stockvault.

Why Certain Drawings Wait 3D

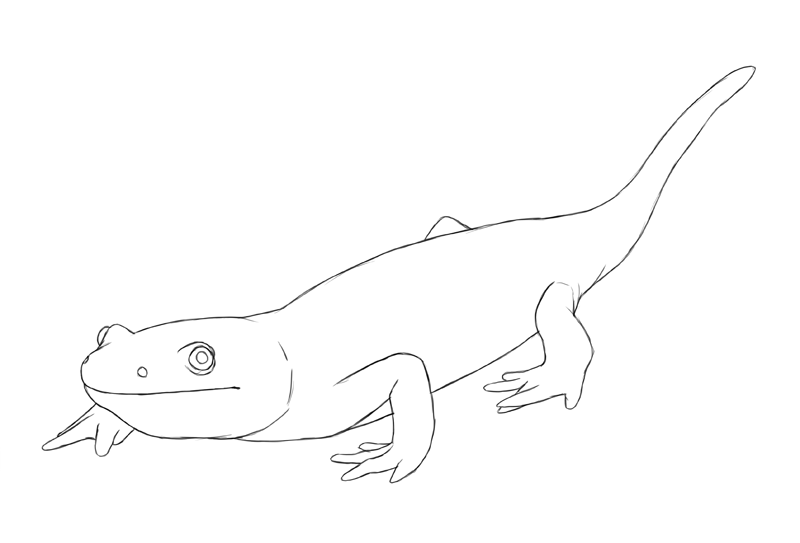

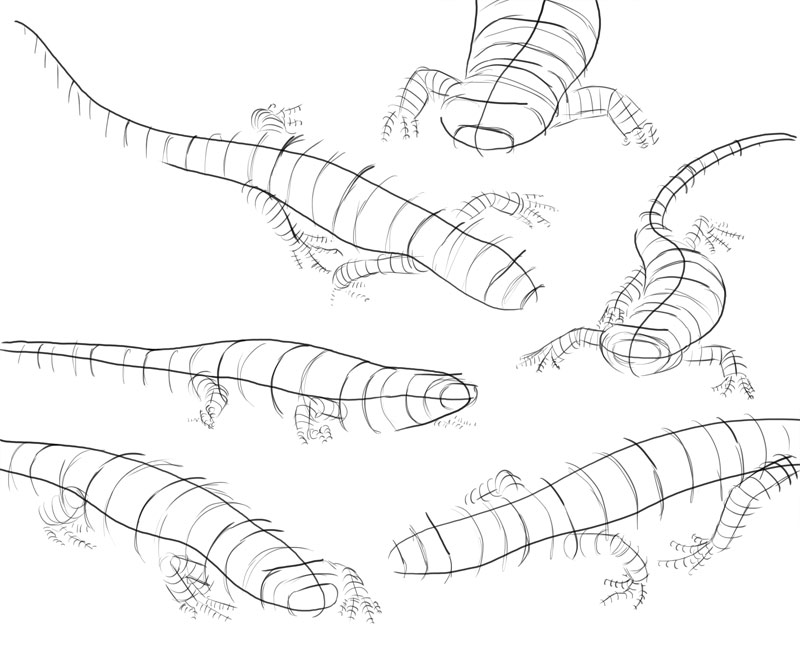

The salamander in this photo looks pretty three-dimensional, right? Let's turn it into lines now.

Hm, something's wrong here. The lines are definitely correct (I traced them, after all!), only the drawing itself looks pretty flat. Certain, it lacks shading, only what if I told you lot that you can depict three-dimensionally without shading?

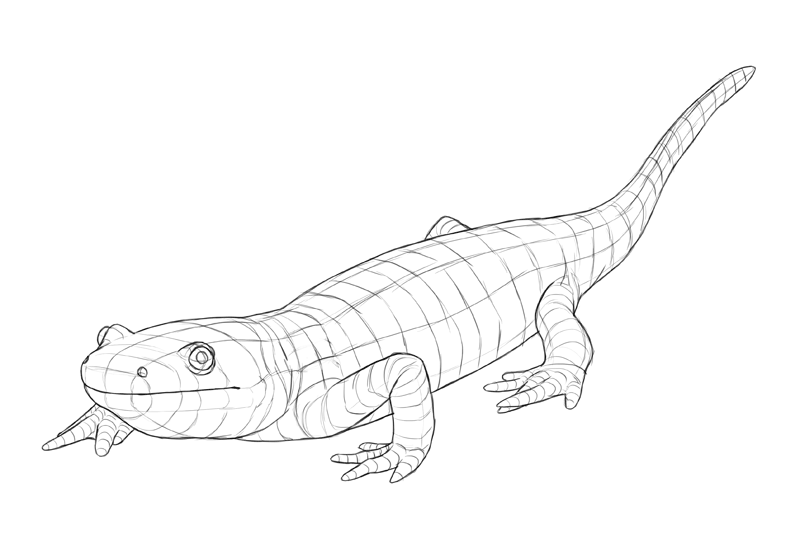

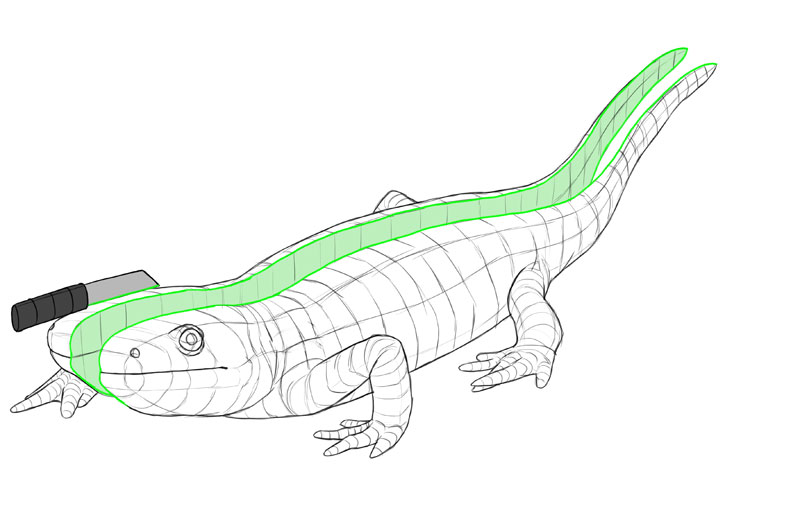

I've added a couple more than lines and… magic happened! At present information technology looks very much 3D, maybe even more the photo!

Although you don't encounter these lines in a terminal drawing, they impact the shape of the pattern, peel folds, and even shading. They are the key to recognizing the 3D shape of something. And then the question is: where practise they come up from and how to imagine them properly?

3D = 3 Sides

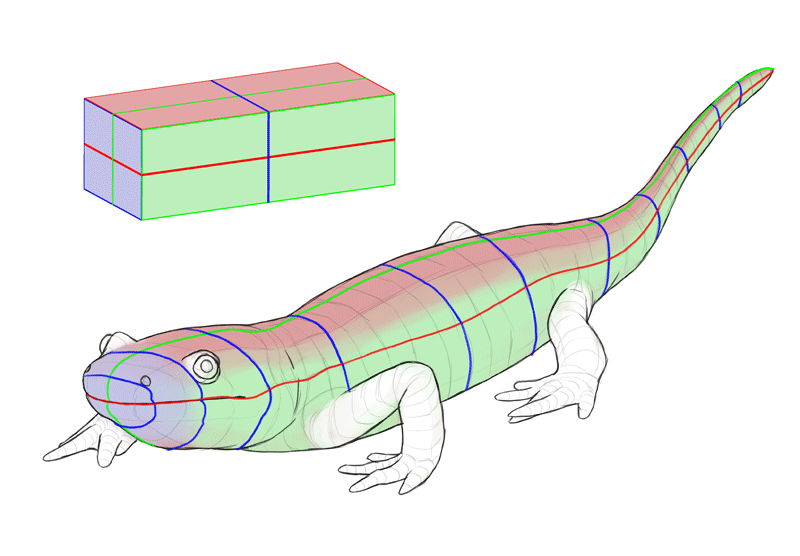

As you think from school, 3D solids have cross-sections. Because our salamander is 3D, it has cantankerous-sections every bit well. So these lines are cipher less, nothing more, than outlines of the body'southward cross-sections. Here'southward the proof:

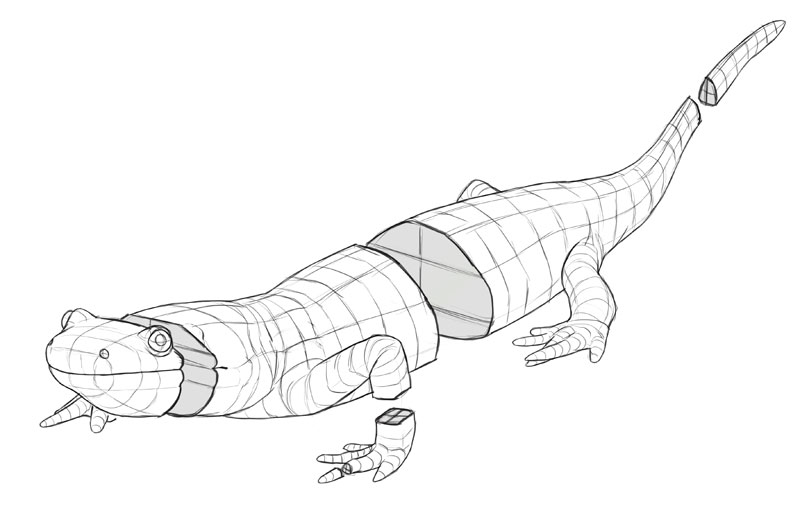

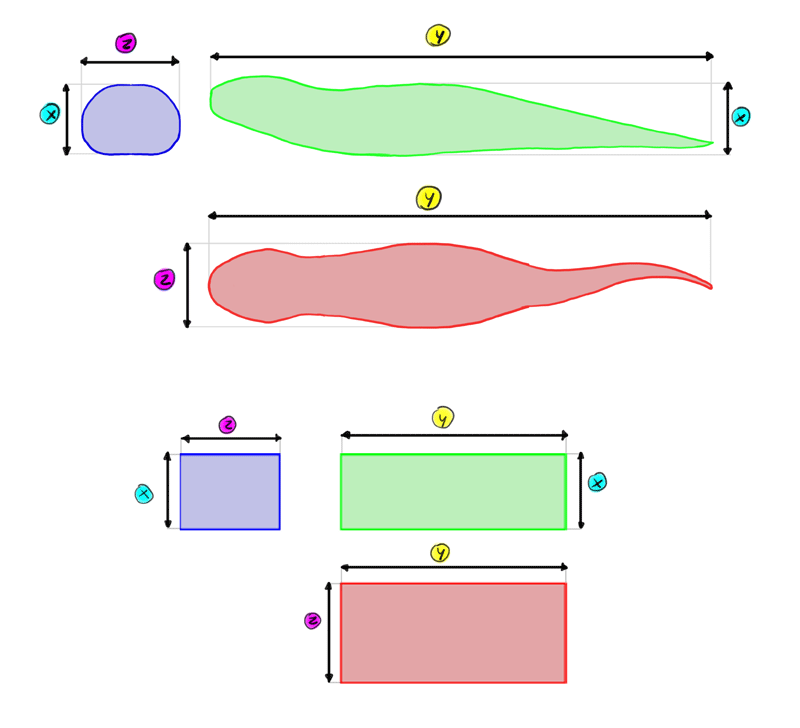

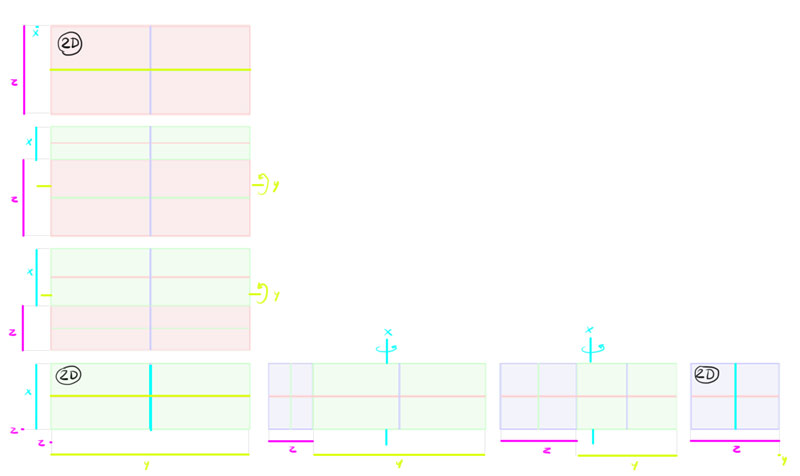

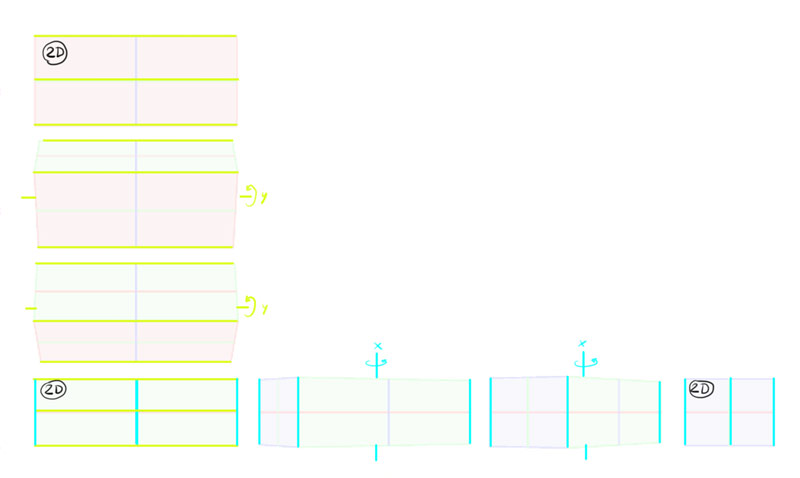

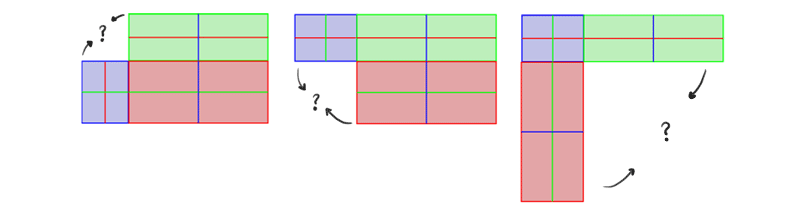

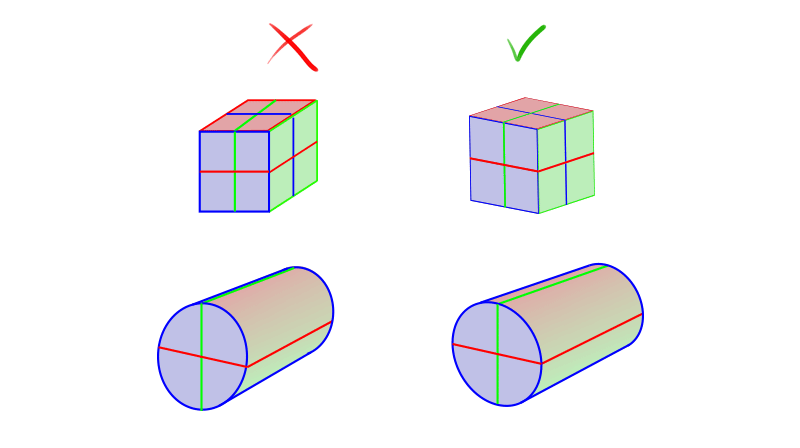

A 3D object tin can be "cutting" in 3 dissimilar ways, creating three cross-sections perpendicular to each other.

Each cross-section is 2nd—which means it has two dimensions. Each 1 of these dimensions is shared with one of the other cross-sections. In other words, 2D + 2d + second = 3D!

And then, a 3D object has iii 2D cross-sections. These three cross-sections are basically three views of the object—here the green one is a side view, the blue one is the forepart/back view, and the red i is the superlative/bottom view.

Therefore, a cartoon looks 2nd if yous can only see one or two dimensions. To make it look 3D, yous need to show all three dimensions at the same time.

To brand it even simpler: an object looks 3D if y'all can meet at least 2 of its sides at the aforementioned time. Here you can meet the top, the side, and the front of the salamander, and thus it looks 3D.

But wait, what'south going on here?

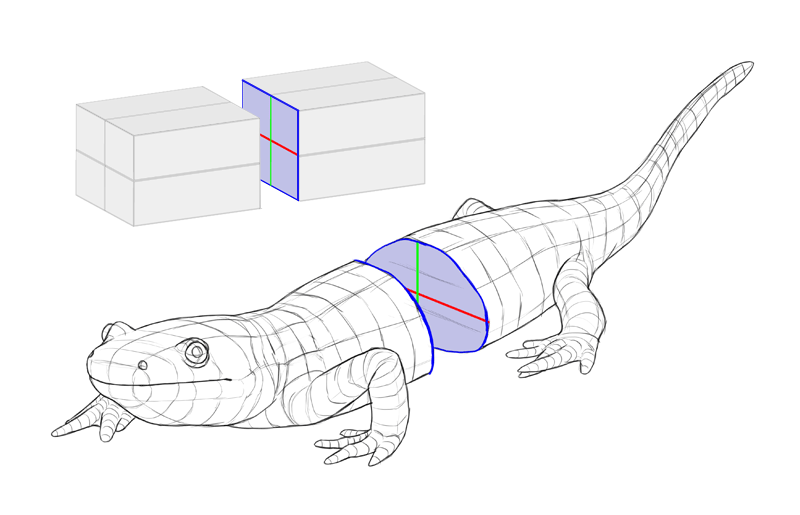

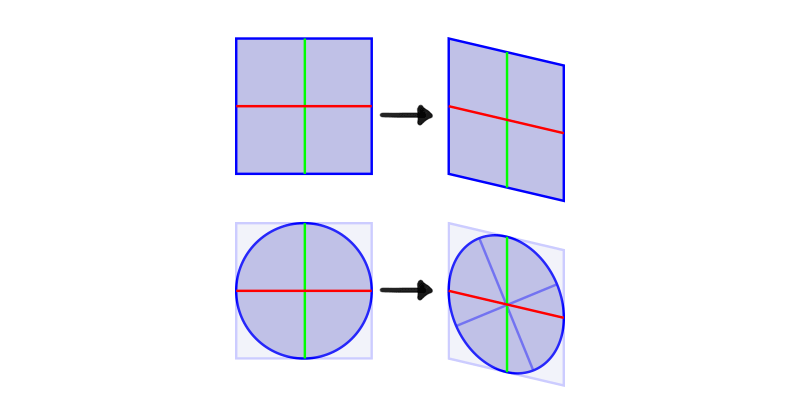

When you look at a 2d cross-section, its dimensions are perpendicular to each other—there's right bending between them. Simply when the same cross-section is seen in a 3D view, the angle changes—the dimension lines stretch the outline of the cross-section.

Let'due south exercise a quick epitomize. A single cross-section is like shooting fish in a barrel to imagine, but information technology looks flat, considering it's second. To make an object expect 3D, you need to show at least 2 of its cross-sections. But when you lot describe two or more cross-sections at once, their shape changes.

This change is non random. In fact, it is exactly what your brain analyzes to empathise the view. And then there are rules of this modify that your hidden mind already knows—and now I'm going to teach your conscious self what they are.

The Rules of Perspective

Here are a couple of different views of the same salamander. I take marked the outlines of all three cross-sections wherever they were visible. I've also marked the top, side, and front. Take a skillful wait at them. How does each view affect the shape of the cross-sections?

In a second view, y'all take two dimensions at 100% of their length, and ane invisible dimension at 0% of its length. If you use i of the dimensions as an axis of rotation and rotate the object, the other visible dimension will give some of its length to the invisible one. If you proceed rotating, one volition keep losing, and the other volition keep gaining, until finally the first 1 becomes invisible (0% length) and the other reaches its full length.

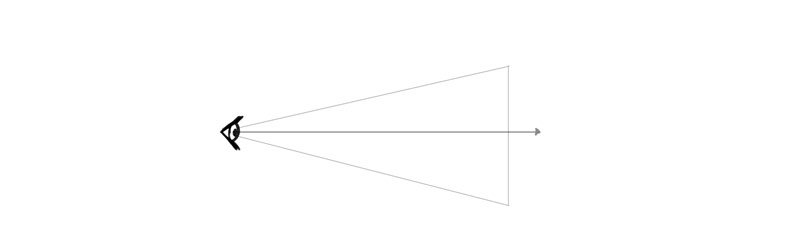

But… don't these 3D views wait a picayune… flat? That'due south right—there's i more thing that we need to accept into account hither. At that place's something chosen "cone of vision"—the further you lot look, the wider your field of vision is.

Because of this, y'all can cover the whole world with your paw if you identify it right in forepart of your eyes, merely information technology stops working like that when y'all move it "deeper" within the cone (farther from your eyes). This also leads to a visual change of size—the farther the object is, the smaller information technology looks (the less of your field of vision it covers).

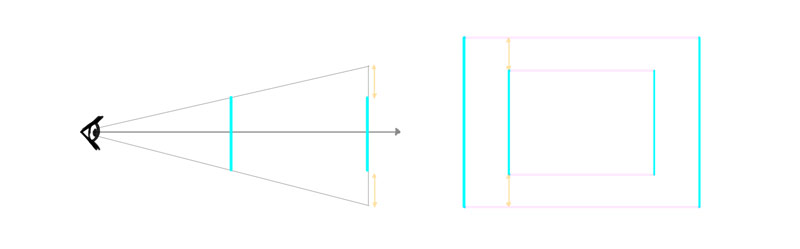

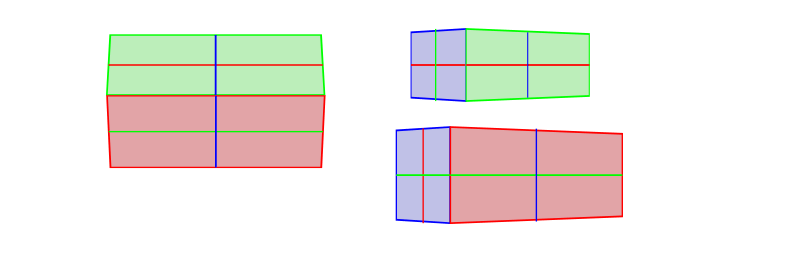

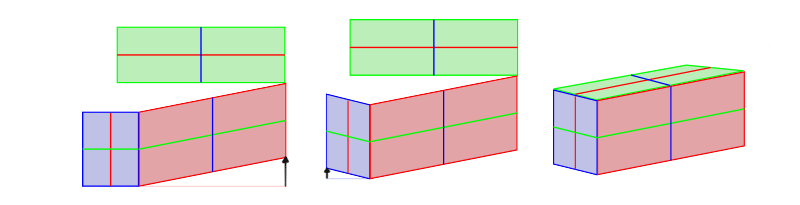

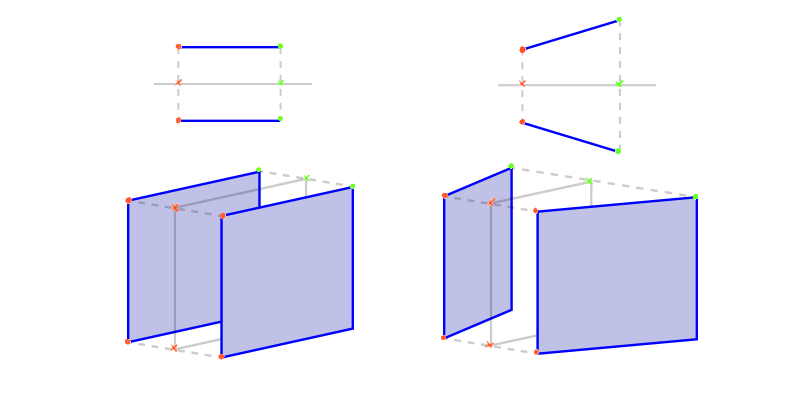

At present lets turn these two planes into two sides of a box by connecting them with the tertiary dimension. Surprise—that third dimension is no longer perpendicular to the others!

So this is how our diagram should really look. The dimension that is the axis of rotation changes, in the end—the edge that is closer to the viewer should be longer than the others.

It's important to remember though that this effects is based on the distance betwixt both sides of the object. If both sides are pretty close to each other (relative to the viewer), this result may be negligible. On the other paw, some photographic camera lenses tin exaggerate it.

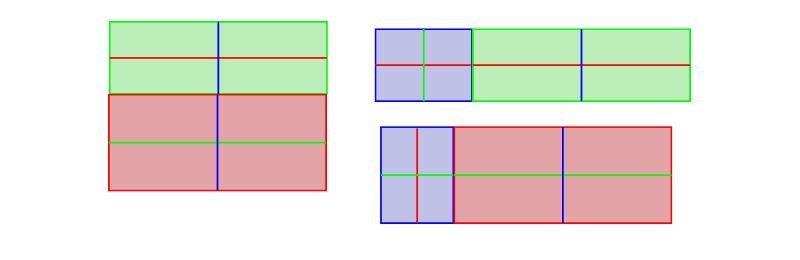

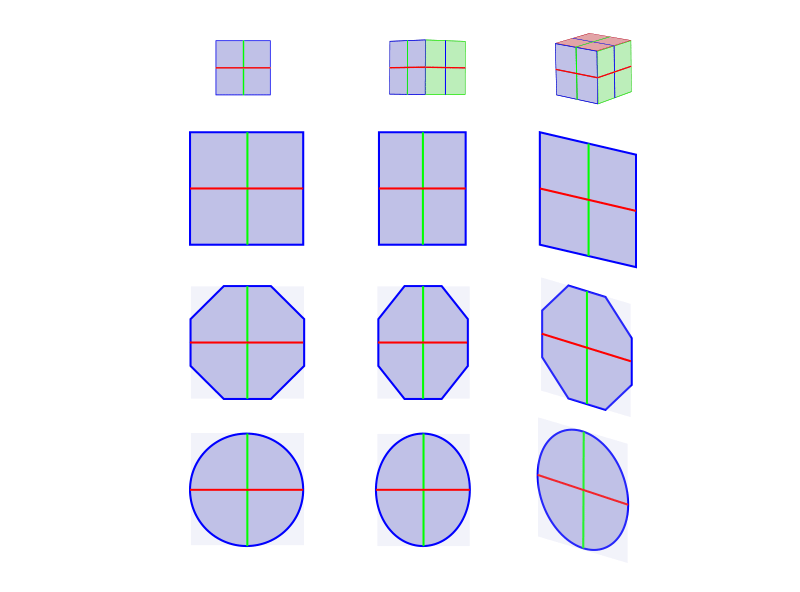

So, to depict a 3D view with ii sides visible, you place these sides together…

… resize them accordingly (the more of one you want to show, the less of the other should exist visible)…

… and make the edges that are farther from the viewer than the others shorter.

Here's how it looks in practice:

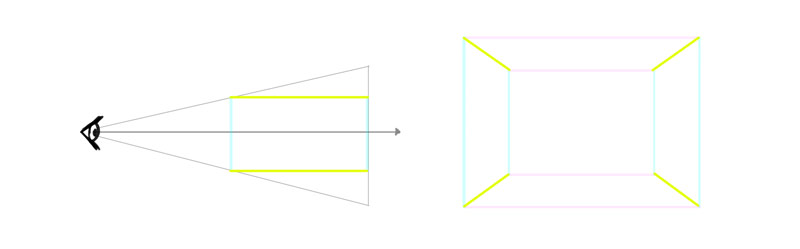

Merely what well-nigh the third side? It's incommunicable to stick it to both edges of the other sides at the same time! Or is information technology?

The solution is pretty straightforward: stop trying to keep all the angles right at all costs. Slant one side, then the other, then make the 3rd one parallel to them. Easy!

And, of course, let's not forget most making the more distant edges shorter. This isn't ever necessary, simply it's good to know how to do it:

Ok, and so y'all need to slant the sides, but how much? This is where I could pull out a whole set of diagrams explaining this mathematically, only the truth is, I don't do math when drawing. My formula is: the more you camber one side, the less you slant the other. Just look at our salamanders again and check information technology for yourself!

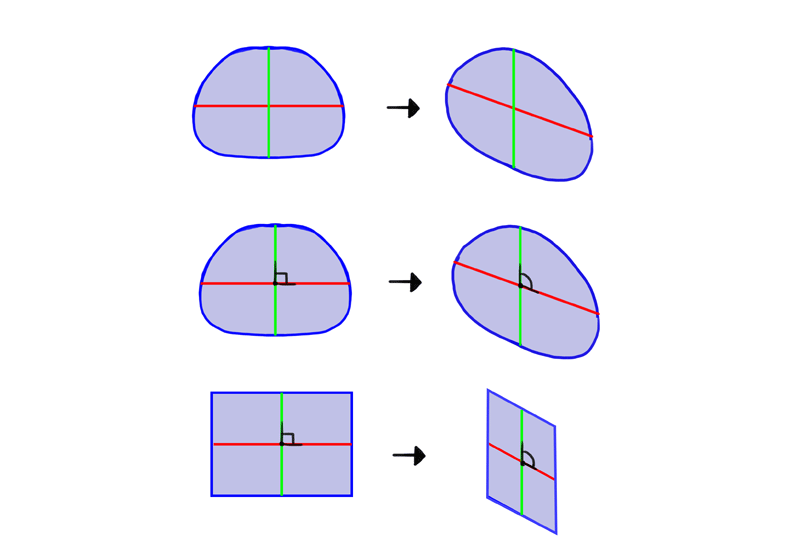

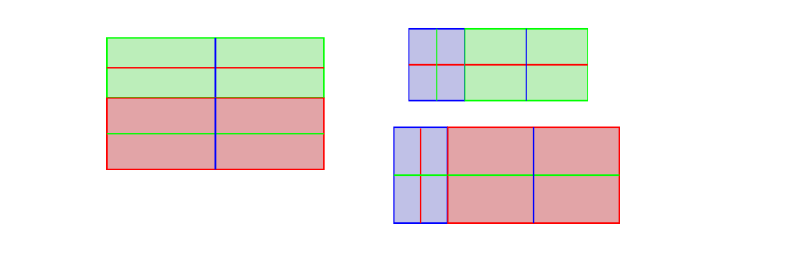

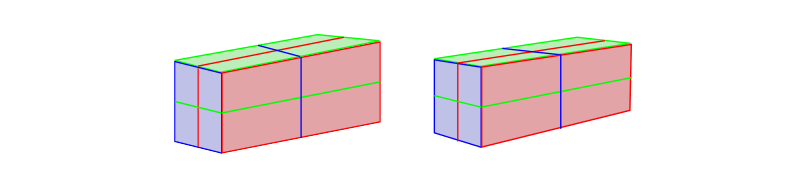

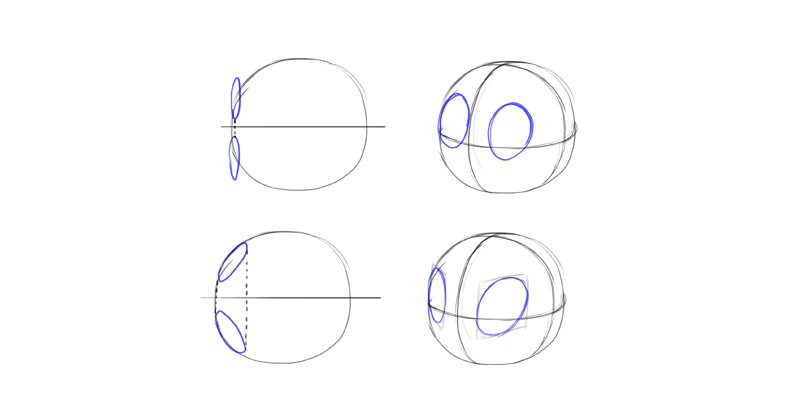

But if you want to draw creatures like our salamander, their cross-sections don't really resemble a square. They're closer to a circle. Just like a square turns into a rectangle when a second side is visible, a circle turns into an ellipse. But that'due south not the end of it. When the 3rd side is visible and the rectangle gets slanted, the ellipse must get slanted too!

How to slant an ellipse? Just rotate information technology!

This diagram tin aid you lot memorize it:

Multiple Objects

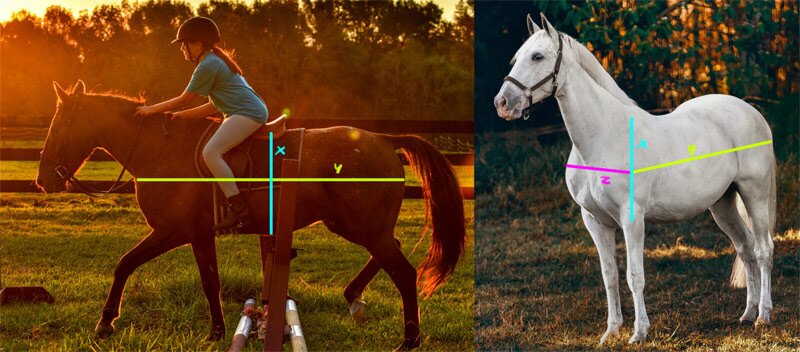

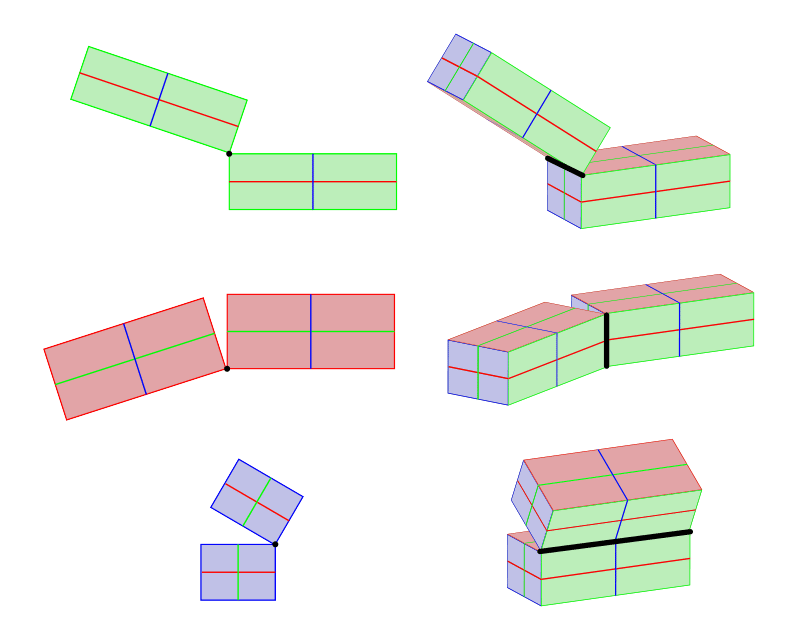

So far we've just talked near drawing a single object. If you lot desire to describe ii or more objects in the same scene, there'due south usually some kind of relation betwixt them. To show this relation properly, make up one's mind which dimension is the axis of rotation—this dimension will stay parallel in both objects. One time you lot do it, yous can exercise whatever you want with the other 2 dimensions, every bit long as you follow the rules explained earlier.

In other words, if something is parallel in one view, then it must stay parallel in the other. This is the easiest way to check if you got your perspective right!

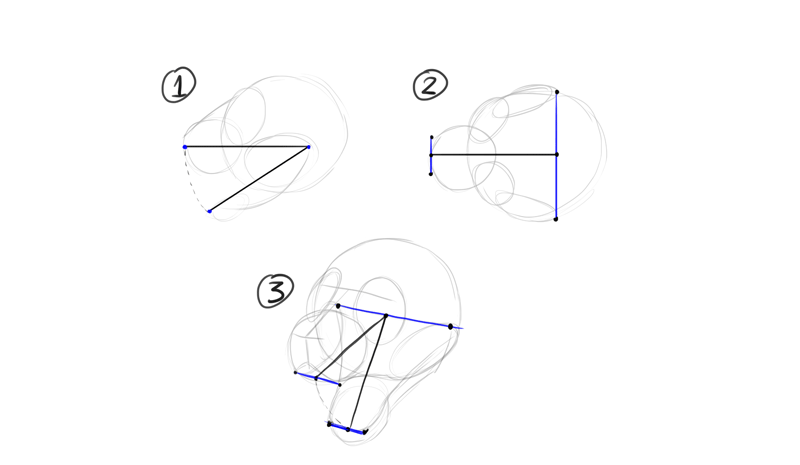

There'southward another type of relation, called symmetry. In 2d the axis of symmetry is a line, in 3D—it'due south a aeroplane. Simply it works just the same!

You don't need to draw the plane of symmetry, only y'all should exist able to imagine information technology right betwixt two symmetrical objects.

Symmetry will help you lot with hard drawing, like a caput with open jaws. Here figure one shows the angle of jaws, figure 2 shows the axis of symmetry, and figure 3 combines both.

3D Cartoon in Practice

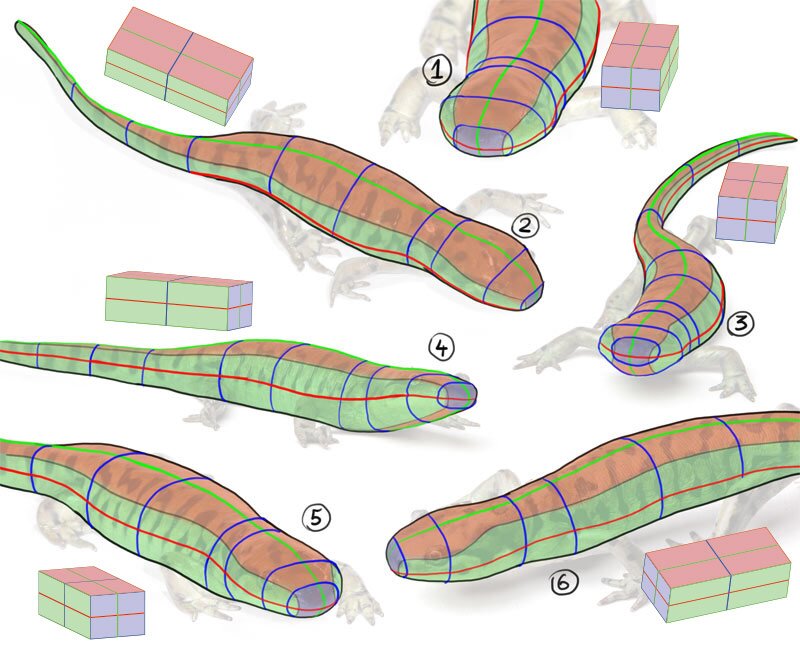

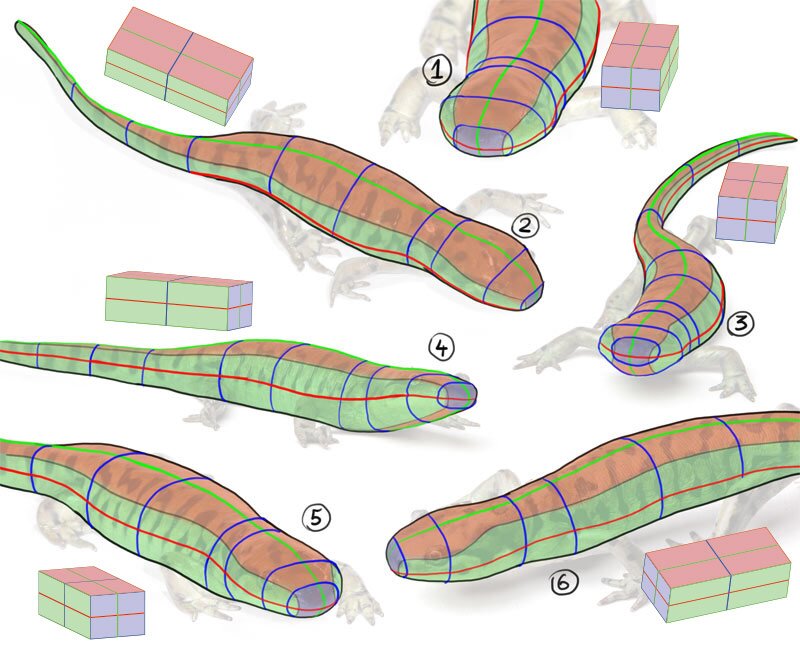

Practice ane

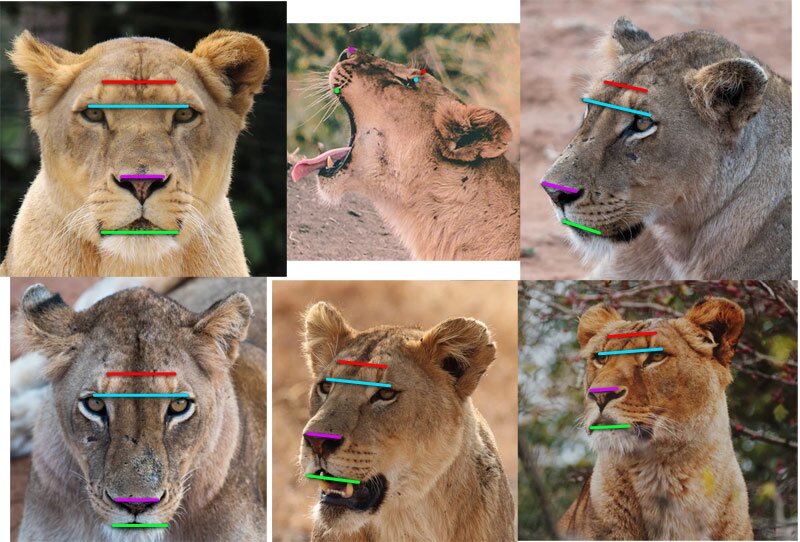

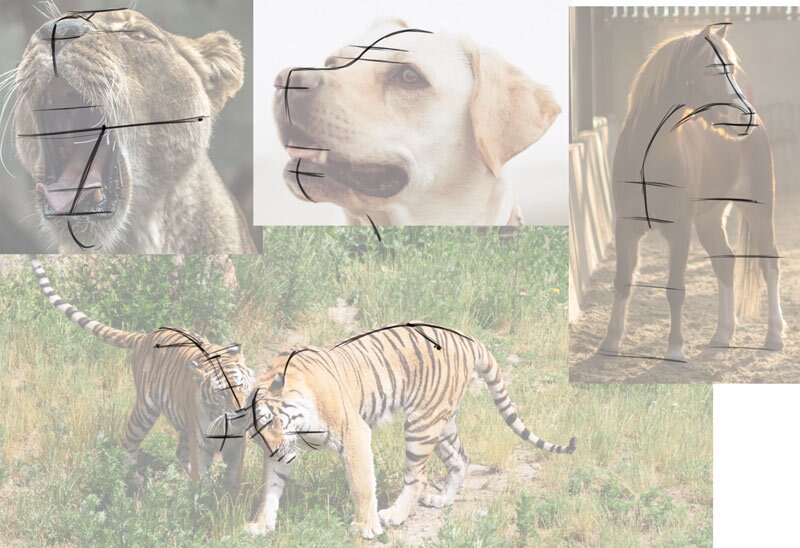

To understand it all better, you can endeavour to find the cantankerous-sections on your ain now, drawing them on photos of real objects. Beginning, "cut" the object horizontally and vertically into halves.

Now, detect a pair of symmetrical elements in the object, and connect them with a line. This volition be the tertiary dimension.

Once you have this management, you tin draw information technology all over the object.

Keep cartoon these lines, going all around the object—connecting the horizontal and vertical cross-sections. The shape of these lines should exist based on the shape of the third cantankerous-department.

In one case you lot're done with the big shapes, you tin can exercise on the smaller ones.

You'll soon find that these lines are all you lot need to draw a 3D shape!

Do 2

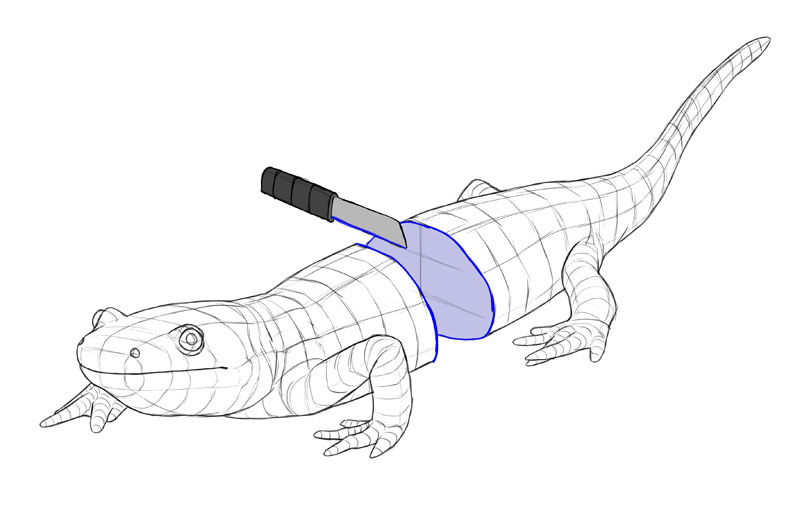

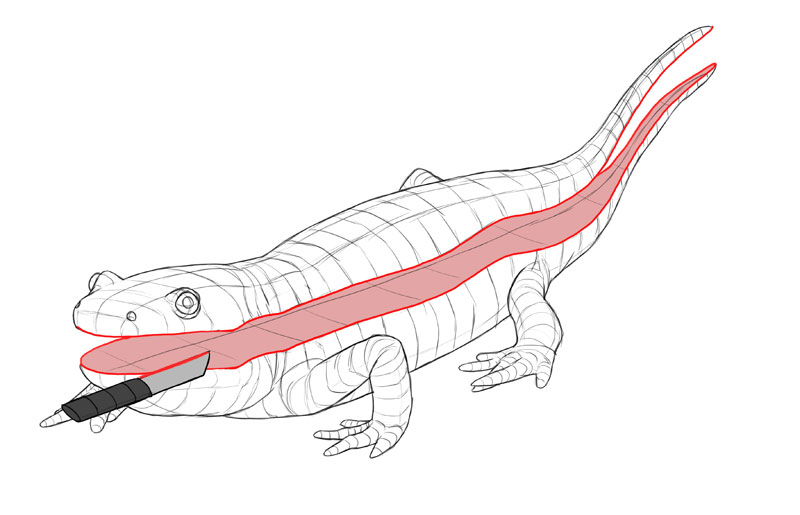

You can do a similar exercise with more circuitous shapes, to better understand how to draw them yourself. Beginning, connect corresponding points from both sides of the trunk—everything that would be symmetrical in top view.

Mark the line of symmetry crossing the whole body.

Finally, endeavour to find all the unproblematic shapes that build the final form of the trunk.

At present yous accept a perfect recipe for drawing a similar animal on your own, in 3D!

My Process

I gave you all the information you demand to draw 3D objects from imagination. At present I'thousand going to bear witness you my own thinking process behind drawing a 3D creature from scratch, using the cognition I presented to you today.

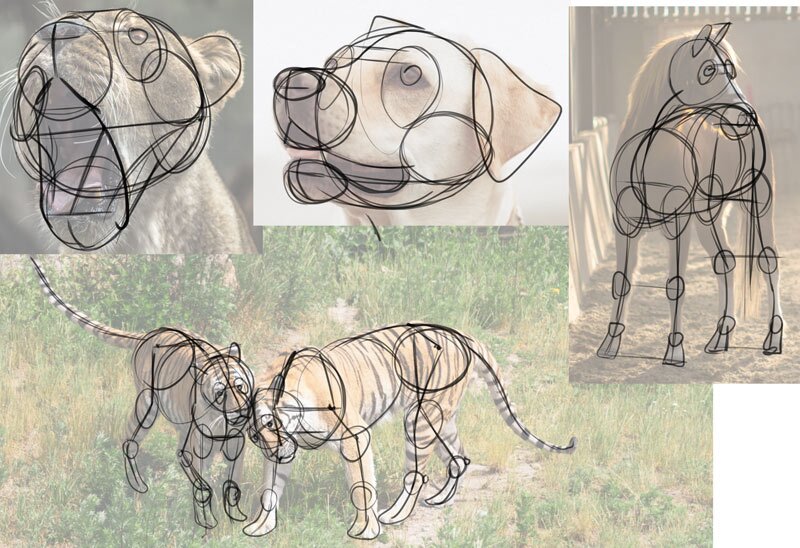

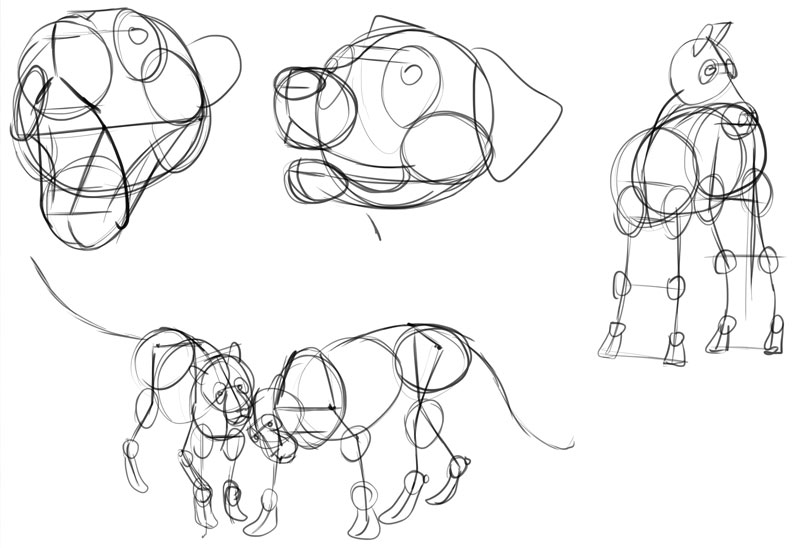

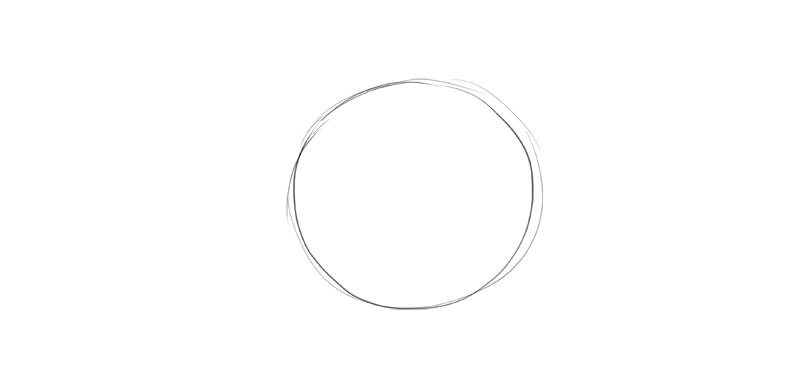

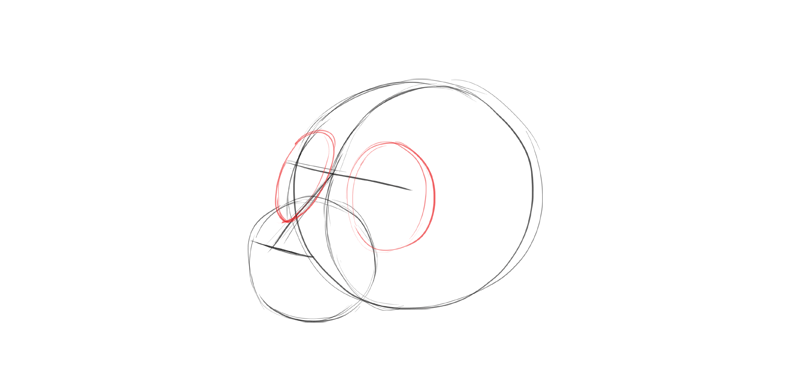

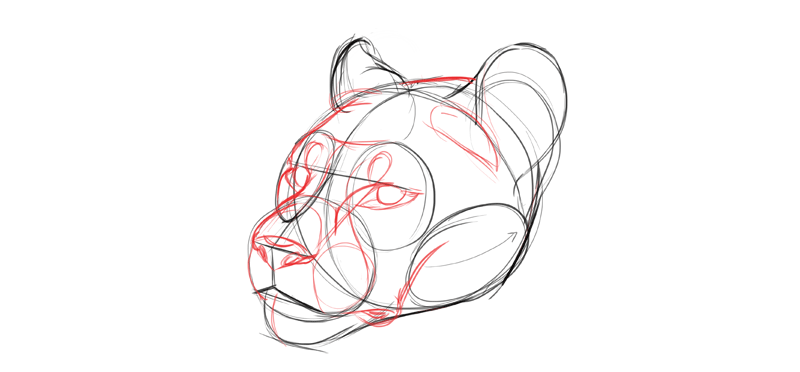

I usually start drawing an fauna head with a circle. This circle should contain the cranium and the cheeks.

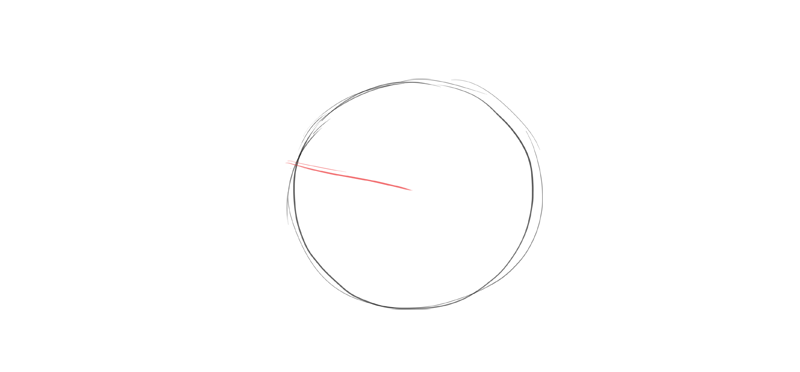

Adjacent, I draw the eye line. It's entirely my conclusion where I want to place it and at what angle. Simply once I make this decision, everything else must exist adapted to this commencement line.

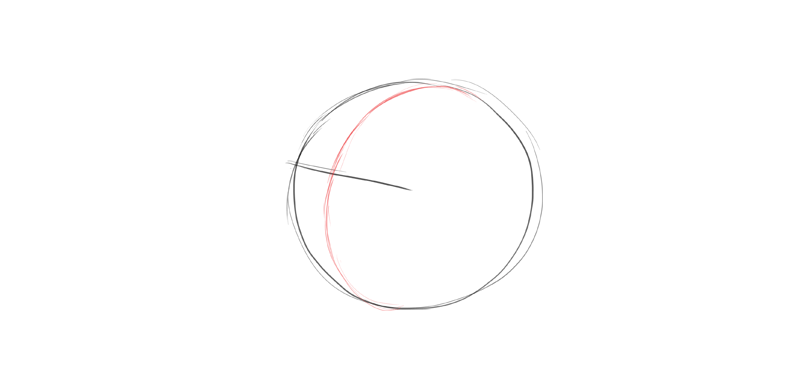

I draw the middle line between the optics, to visually divide the sphere into two sides. Can you notice the shape of a rotated ellipse?

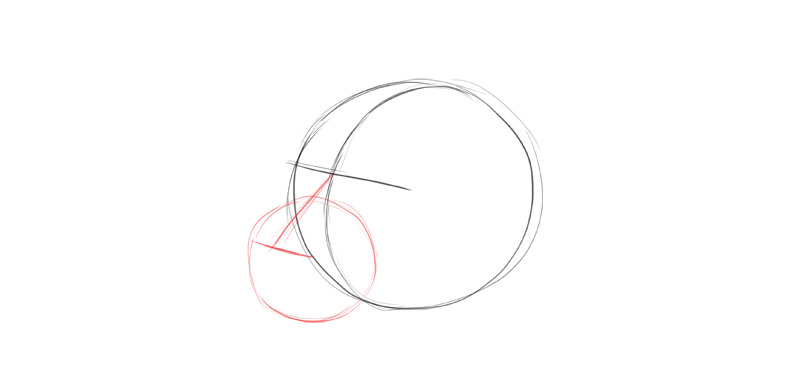

I add another sphere in the front end. This volition exist the muzzle. I detect the proper location for it by drawing the nose at the aforementioned time. The imaginary plane of symmetry should cutting the olfactory organ in half. Also, discover how the nose line stays parallel to the eye line.

I draw the the area of the eye that includes all the bones creating the middle socket. Such big expanse is easy to draw properly, and information technology will help me add together the optics after. Go along in heed that these aren't circles stuck to the front of the confront—they follow the curve of the main sphere, and they're 3D themselves.

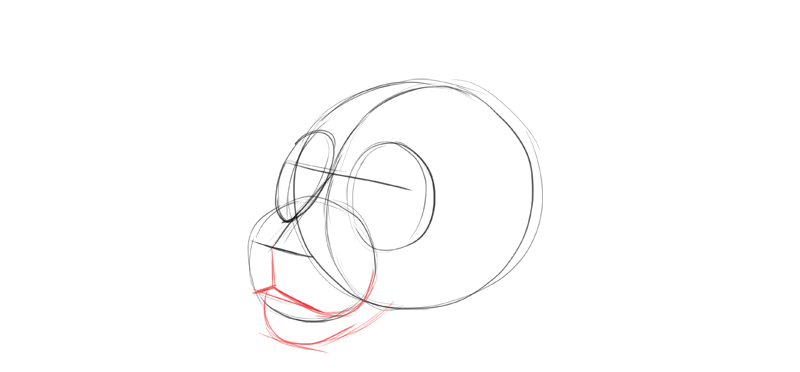

The mouth is so easy to draw at this point! I simply have to follow the management dictated by the eye line and the nose line.

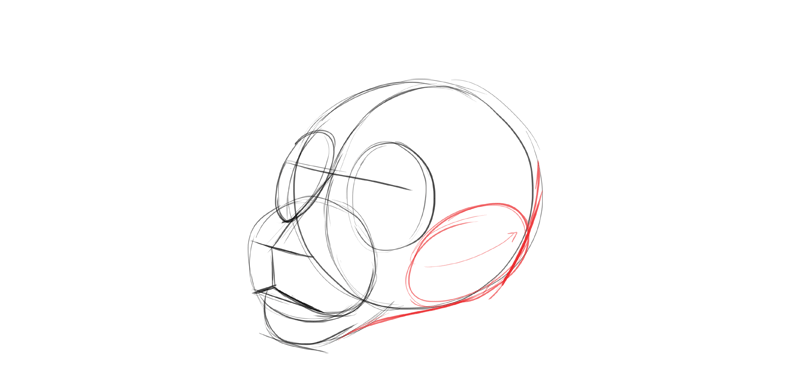

I draw the cheek and connect information technology with the chin creating the jawline. If I wanted to draw open jaws, I would draw both cheeks—the line between them would be the axis of rotation of the jaw.

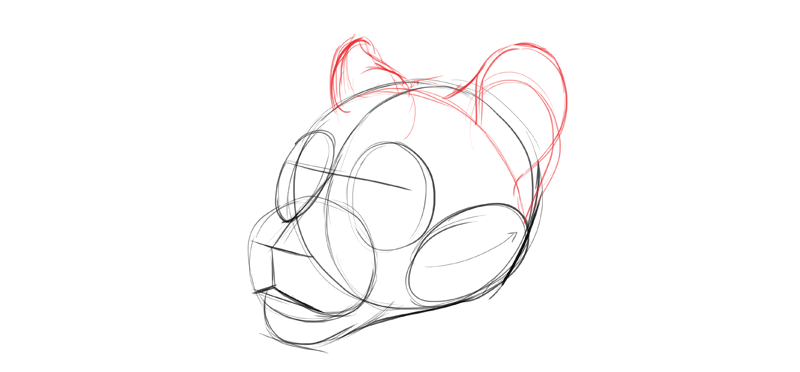

When drawing the ears, I make sure to depict their base of operations on the same level, a line parallel to the eye line, but the tips of the ears don't accept to follow this rule and then strictly—information technology's because usually they're very mobile and tin can rotate in various axes.

At this point, adding the details is as easy as in a 2D drawing.

That'southward All!

Information technology'south the end of this tutorial, but the kickoff of your learning! Y'all should now be set up to follow my How to Describe a Big Cat Caput tutorial, also every bit my other animal tutorials. To do perspective, I recommend animals with simple shaped bodies, like:

- Birds

- Lizards

- Bears

You should also observe it much easier to understand my tutorial about digital shading! And if you want even more exercises focused directly on the topic of perspective, you'll like my older tutorial, full of both theory and exercise.

Source: https://monikazagrobelna.com/2019/11/25/drawing-101-how-to-draw-form-and-volume/

0 Response to "how to draw a 3d marble"

Post a Comment